In her beautiful 1950's cursive handwriting, my mom noted that I received my gamma shot in April 1959 when my brother had red measles, then my second gamma shot in April 1963. Back then, gamma globulin was used as a serum therapy to prevent or mitigate measles infection. Around the same time, I was admitted with pneumonia to the children's hospital, the same hospital at which I would come to lead the responses against future measles outbreaks.

In her beautiful 1950's cursive handwriting, my mom noted that I received my gamma shot in April 1959 when my brother had red measles, then my second gamma shot in April 1963. Back then, gamma globulin was used as a serum therapy to prevent or mitigate measles infection. Around the same time, I was admitted with pneumonia to the children's hospital, the same hospital at which I would come to lead the responses against future measles outbreaks.

While I have no memory of these early events, they were the peak years of measles in the US before the measles vaccine became available in 1963. Parents of kids in the pre-vaccine era will tell you how terrifying it was when measles struck your family and the quarantine sign went up on your front door. For decades after the vaccine was introduced, measles became increasingly rare. Most parents didn't know what it looked like, or, more importantly, what it could do to their children. Because the measles vaccine worked so well and cases became rare, some parents began to worry more about the vaccine than the disease itself.

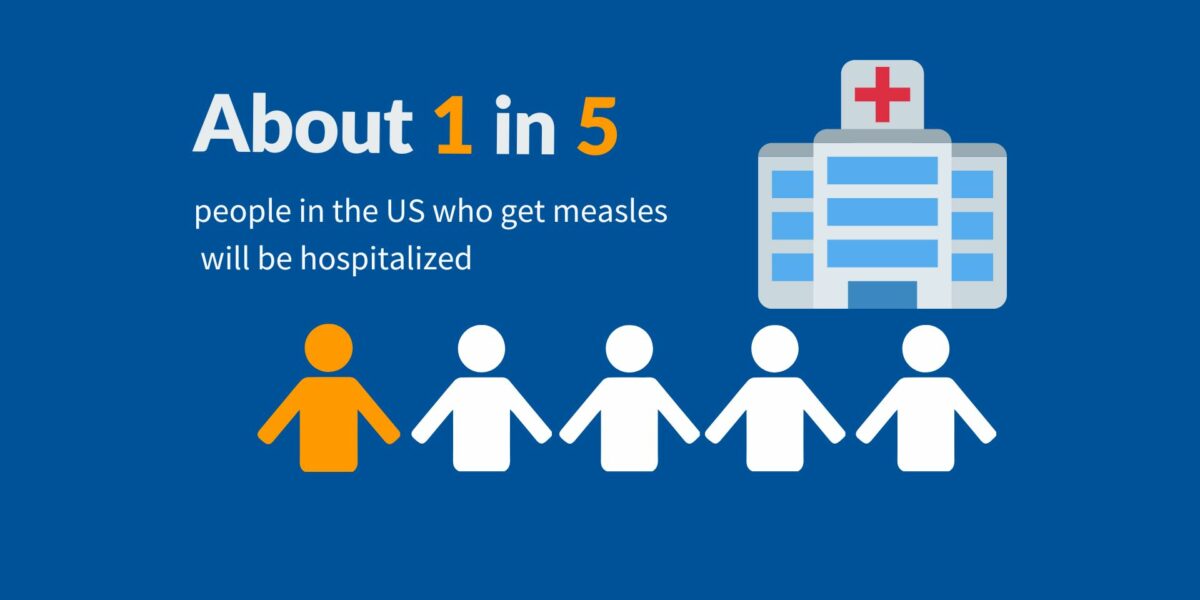

I read about measles in nursing school in the 1970s but never saw a patient with it until after grad school in the early 1990s. That was when the US was hit with a nationwide measles outbreak following a drop in pre-school vaccination rates. This outbreak lasted 3 years, caused more than 55,000 cases, and led to more than 120 deaths, mostly in unvaccinated young children. It hit hard in St. Paul, MN, where I lived, with more than 440 cases and the deaths of 3 young children, all of whom came too late for care. But keep in mind, before the vaccine, there were about 3-4 million measles cases, 48,000 children hospitalized, and up to 500 deaths every year in the US.

Working at Children's Hospital of St. Paul, seeing the deaths from measles and so many sick kids and frightened parents in 1990-the year I became a mother-changed me and the trajectory of my career forever. No child should die of a vaccine-preventable disease. The hospital had to be in full infection-control emergency mode to prevent measles from spreading.

This period also led to several effective public health interventions: adding a second dose of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine at kindergarten to protect the roughly 5% of people who did not respond to the first dose; establishing the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program so cost would not be a barrier to vaccination; and increasing awareness among healthcare professionals of the importance of treating every visit as a vaccine visit to avoid missing children who are behind on recommended vaccines and to emphasize pre-school vaccination.

Together, these actions helped reverse one of the largest measles outbreaks in modern memory and led to the achievement of US measles elimination in 2000.

Measles Makes a Comeback

However, as the internet flourished, so did misinformation about measles and the MMR vaccine, leading to false fears that the vaccine causes autism-a myth that has been thoroughly disproven. By 2017, the Minneapolis MMR vaccination rate plummeted from more than 90% vaccinated to only 42% of 2-year-olds, with the hardest hit community being Somali preschool children. By spring, another infectious disease emergency was underway at Children's Hospital of Minnesota. The 75 cases of measles gained national attention.

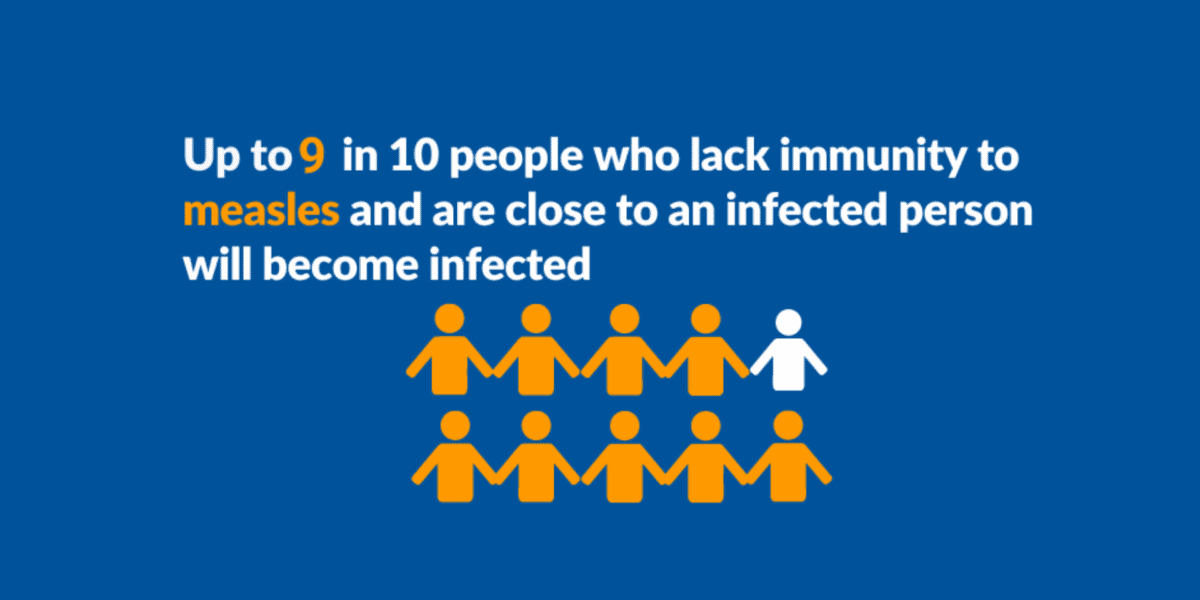

How does measles come back after being eliminated? Vaccination is an ongoing process. If not maintained, diseases like measles can reappear when introduced by travelers to unvaccinated communities, as seen in Minneapolis. The fewer people vaccinated, the greater that outbreak will be.

After seeing many children with measles, I could recognize it across the lobby of the bustling emergency room: a very weak, miserable, sick child flopped over his terrified parent’s shoulder, whimpering but so dehydrated that no tears were forming, red hot faced with fever, eyes blinking with pain from just the brightness of the lobby lights, coughing with profuse runny nose, and the characteristic rash spreading from hairline to trunk in a matter of hours.

Many of these children were admitted to the hospital because they had pneumonia or encephalitis (brain swelling) that was so severe they could not breathe well on their own. They received IV rehydration and ventilation, but not anti-viral medications, as there are none that treat measles. Talking with dozens of parents, their regret and shame for not vaccinating their children against measles was profound. They would tell me things like, "All I want him to do is wake up, please wake up," or "I would have vaccinated her if I knew she was going to be this sick, I didn't know," or "I was told not to do the triple shot (MMR) when I came to this country or it would make him autistic, now I am afraid of measles." As a nurse practitioner and a parent myself, I felt heartsick for the parents who skipped vaccination only to see what the disease they could have prevented is really like.

I share my experiences and the voices of parents at their sick child's bedside so parents today-in yet another worldwide resurgence of measles due to misinformation and disinformation-will listen to people who know measles firsthand. The clinicians who recommend vaccination want the same thing the parents do: safety and good health for children. When parents ask me what to do about vaccination, I tell them that the safest thing to vaccinate their children, to safely, knowingly prevent serious diseases. Letting children go unvaccinated means taking an unnecessary and potentially fatal risk.

I could recognize measles across the bustling emergency room lobby: a weak, miserable, sick child flopped over his terrified parent’s shoulder, whimpering but so dehydrated that no tears were forming, red hot faced with fever, eyes blinking with pain from the brightness of the lobby lights, coughing with a runny nose, and the characteristic rash.

Patsy’s Advice

Measles is a very serious disease, sometimes fatal, sometimes life-changing, and always preventable with vaccination. Do not delay. Get every 12-month-old their MMR vaccine.

Comparta su historia

Comparta su historia para ayudar a otras personas a comprender mejor el impacto que tienen las enfermedades prevenibles mediante vacunas, las infecciones resistentes a los medicamentos y otras enfermedades infecciosas.

Recursos relacionados

Preguntas frecuentes sobre el sarampión

Respuestas a preguntas comunes sobre el sarampión, el virus más contagioso conocido por la humanidad

Alerta de sarampión

En este episodio, los expertos de la NFID ofrecen información sobre el reciente aumento de casos de sarampión, una enfermedad altamente contagiosa y potencialmente grave que ahora está de regreso debido a las bajas tasas de vacunación en algunas comunidades…

Recursos de concientización sobre el sarampión y ejemplos de publicaciones en redes sociales

Recursos y ejemplos de publicaciones en las redes sociales para crear conciencia sobre la importancia de prevenir el sarampión